By Grant Walkin

A look at today’s building envelopes (Part 1: Air sealing is king)

Canadian ContractorBuilding durability and indoor air quality requires increased focus on air leakage

Canadian Contractor is pleased to publish the first of three articles by Grant Walkin, a building envelope specialist, focusing on the science behind today’s energy-efficient homes.

Air sealing a building envelope is an important factor for energy efficiency and occupant comfort. A drafty room will feel cold in winter, even if the thermometer is set to 21°C. Air leakage also contributes to high energy bills. However, as we insulate by packing more and more fluffy stuff in the walls or other means responding to increased demands for greater performance from buildings, air sealing becomes more critical for two other important factors — building durability and indoor air quality.

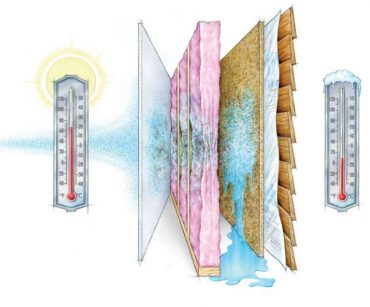

Figure 1 (Gibson 2010)

Why? It’s about water vapour. Air holds tiny water droplets called water vapour. The amount of water droplets a given volume of air can hold depends on temperature – the warmer the air, the more water vapour it can hold, and vice versa. At 100 per cent relative humidity, the air is fully saturated with the tiny water droplets relative to the air temperature. Warm up that air and the RH drops. Cool that air, or allow the 100 per cent RH air to come into contact with a surface cooler than the air, and water droplets will form. This is called condensation, or dew. The dew point of air is the temperature where the RH has surpassed 100 per cent. Think about a cold pop can sitting outside on a hot summer day and how the condensation forms on the outside of the can. A building acts the same way in the winter, like an inside-out coke can — hot and humid on the inside. In winter when it’s cold outside, condensation forms on the inside when warm moist indoor air escapes to the cool outside through holes – like leaky doors and windows, around unsealed wall penetrations, and even through the wall itself. Condensation on windows is a great demonstration of this. In the summer, the situation is reversed except it is warm, moist outdoor air.

As air moves across the building envelope, so does water vapor. If dew point occurs during this transition, water droplets will form within the building envelope, Figure 1 (Gibson, 2010), sometimes referred to as interstitial condensation.

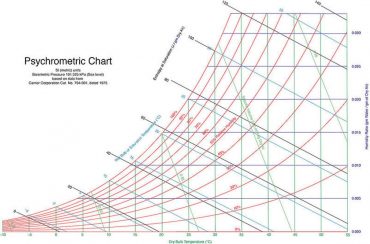

Figure 2

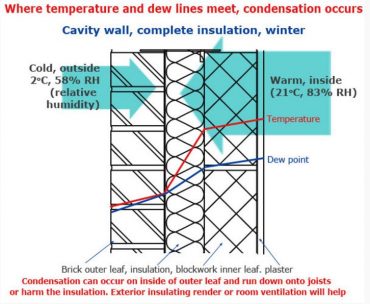

How do we know if, or where, the dew point will occur? We could analyze the wall section with a psychrometric chart, Figure 2, and trace the air’s relative humidity as it passes through the envelope, Figure 3 (Doggart, 2012) – or hire a building science specialist to do it. Chances are, if the building is occupied and you have air leakage, you have condensate forming that may lead to a problem. That can lead to water staining, material deterioration, and mold – resulting in poor aesthetics, structural problems, and reduced indoor air quality, respectively. It is likely that interstitial condensation may be occurring without the occupant even realizing it.

The function of the building can also be directly related to the root cause of condensation. Inhabitants produce water vapour through breathing, perspiring, showering, cooking, etc. The more water vapour produced, the greater the risk of condensation forming from a leaky building envelope. This can impact durability. My university professor once told me that the most durable building was a vacant building.

Figure 3 (Doggart 2012)

Older buildings (100+ years) were relatively drafty. They usually did not have a problem with condensation forming within the walls, because they were poorly insulated, often with not much more than a handful of old newspapers. The lack of insulation allowed air to move across the envelope and dry out. Those drafty envelopes also allowed the humid interior air to be quickly displaced by cool, dry air during the winter months, thereby not allowing humidity levels to build up. Radiators were placed in front of windows and beside doors to prevent condensate from forming on the cold single pane glass. Today, you still see heat registers and radiators at those locations, at least in all but the high performance buildings. That’s because high performance buildings are well insulated, with very good windows and doors, and … air tight!

How big a problem is air leakage? This depends on the makeup of the building’s envelope. Here are some questions to consider:

- Thermal Bridging: Are there conductive materials such as concrete, aluminum, or steel bypassing the insulation layer? This will increase the risk of cold surfaces and subsequently condensation.

- Material Types: Are there moisture-sensitive materials such as wood or drywall that will degrade with moisture or promote bacterial growth when exposed to moisture?

- Insulation Types: Is the building solely insulated with fiberglass batt insulation without an effective air barrier or vapour retarder to prevent dew point from occurring within the wall? Or is the building wrapped with exterior rigid insulation so that moisture-rich air cannot reach dew point and therefore have no adverse effects?

- Location: Is there air leakage around a steel door where condensate can pool on an aluminium sill, or is it occurring through a wood framed wall packed with fiberglass batt insulation?

A probable reason why we do not see more widespread problems with condensation and rot in walls is that building components can to some degree buffer some moisture until conditions change, allowing materials to dry out again. In Canada and the United States, we tend to construct our residential buildings with wood. Wood is a hygroscopic material, meaning that it can readily absorb and release moisture. Wood as a buffer will absorb moisture up until it hits saturation point, after which rot and mould growth can occur.

Understanding the importance of air sealing along with the risks of interstitial condensation forming within walls is critical in designing a highly insulated high performance building. If it is not, the results could be disastrous leading to very expensive and disruptive repairs – and not to mention the accompanying headaches.

Grant Walkin (MsC., P.Eng) is a building envelope and structural glass engineer at Entuitive Corp. in Toronto that specializes in commercial, institutional, and residential high performance buildings.

Grant Walkin (MsC., P.Eng) is a building envelope and structural glass engineer at Entuitive Corp. in Toronto that specializes in commercial, institutional, and residential high performance buildings.

References

Advertisement

Print this page

1 Comment » for A look at today’s building envelopes (Part 1: Air sealing is king)

1 Pings/Trackbacks for "A look at today’s building envelopes (Part 1: Air sealing is king)"

-

[…] Parts One & Two of Grant’s series on building envelopes Part One: Air sealing is king Part Two: Do buildings need to […]

Air sealing may be the key to comfort and energy efficiency but moisture control from inside and out is the key to durability. Water is our lifeblood but also our greatest adversary. Excellent article though. This is why competent architect/designer/engineer/contractor team is imperative.