By Jack Kazmierski

Unintended consequences: Quest for energy-efficient homes could be killing Canadians

Canadian Contractor Project Management Smart House canadian contractor magazine Casey Edge contractor energy efficient home Kelley Bush National Building Code radon radon poisoningThe Law of Unintended Consequences applies to everything from economic policies to social change and even the design and construction of Canadian homes. A good example is the way in which a tighter building envelope can result in unwanted mold, or even a much deadlier unintended consequence: radon exposure.

According to Health Canada, long-term exposure to radon is the number-one cause of lung cancer for non-smokers.

“Research has shown that energy efficiency can increase indoor radon levels,” Kelley Bush, manager of Radon Education and Awareness at Health Canada told Canadian Contractor. “Research has found that a more recent construction year, greater square footage, fewer storeys, greater ceiling height and reduced window openings are all associated with increased radon in the home.”

Understanding radon

Radon is everywhere. While it’s true that parts of Canada have higher levels of radon than others, all buildings have some radon in them and none should be assumed to be radon-free. “The reason for this,” Bush explains, “is that radon comes from the breakdown of uranium in the ground. And because there’s uranium everywhere in the Earth’s crust, it means that radon gas will seep into all buildings everywhere, unless it’s a home that’s built on stilts, a boat house or a tree house.”

While radon maps offer an overview of where radon levels may be higher across Canada, Bush warns against relying on them. “Even in areas where we know radon is very high, you can go into a neighbourhood, test all the houses and it’ll vary by house,” she explains. “So really, the only way to know for sure is to test.”

The role of the homebuilder

The complexity of the radon problem is further compounded by the fact that it’s impossible to tell whether a building will have elevated levels of radon before it’s actually constructed.

“You have to test after you build the house and you move into it,” Bush adds. “The amount of uranium in the area that you’re living in is a significant contributor, but how the house was built; the ventilation system; how many doors and windows you open throughout the day throughout the month and throughout the year; all affect the amount of radon that is drawn from the ground into the house itself.”

Without knowing which homes will have higher radon levels and which ones won’t, Canadian homebuilders must abide by local building codes in order to mitigate radon issues, should they surface in the future.

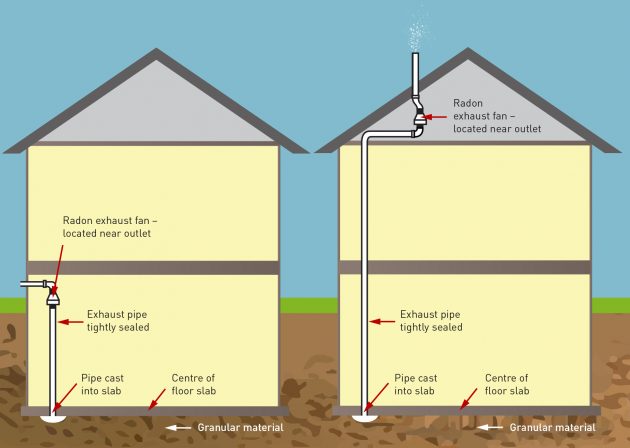

Two recommended options for installing an active soil depressurization system for radon reduction in homes.

National Building Code

The National Building Code of Canada first addressed the radon issue in 2010 and again in 2015, with most provinces and municipalities now adopting recommendations in their Building Codes. Specific requirements for radon are spelled out in subsection 9.13.4 of the NBC, and according to Grace Zhou, senior research officer at the Construction Research Centre at the National Research Council of Canada, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, P.E.I., Nunavut, Northwest Territories and Yukon have adopted NBC 9.13.4. without variations; B.C., Ontario and Quebec have significant technical variations; Newfoundland and Labrador delegates adoption to cities; and New Brunswick has not adopted the 2015 NBC.

The key to effective radon mitigation is an active soil depressurization system. “The current building code requires a minimum four inches of gravel above the soil, and below the concrete slab,” Zhou explains. “On top of that should be a continuous air barrier system. Minimum requirements would be six-millimetre poly, taped and sealed at all the joints, walls and any penetrating points. If the walls are in contact with the soil, an air barrier system is required there as well.”

With new construction, a four-inch PVC pipe that goes from underneath the slab at ground level to the roofline is required in order to draw the radon from under the home to the outside (retrofitted homes can be vented from a nearby wall). “This is basically a rough-in,” explains Ulrik Seward, chief building official and managing chief of approvals, City of Calgary. “The length of pipe is capped off and labeled in case the building owner wants to install a future radon extraction system.”

Seward says that when it comes to radon, Calgary takes the requirements from subsection 9.13.4 of the NBC very seriously. “The pipe is clearly labeled near the cap and if applicable every 1.8 meters, and at every change in direction, to indicate that it is intended only for the removal of radon,” he adds.

Energy efficiency vs. radon

The good news is that energy-efficient homes don’t necessarily have to be radon death traps. “If the walls that are in contact with the soil and the basement floor slab are very well sealed and insulated by materials with low radon permeability, then those energy-saving measures would actually help to reduce the amount of radon coming indoors,” explains Zhou. “However, if radon finds its way into [an airtight] home, and the home is not equipped with mechanical ventilation, then it will be more difficult for radon to escape. So there’s no absolute yes or no. Some energy efficient features will reduce radon gas, and others may make the radon problem worse.”

It’s this sense of uncertainty that has Casey Edge, CEO of the Victoria Residential Builders Association, sounding the alarm about how dangerous it can be for us to continue pushing the energy-efficiency envelope without fully understanding the full consequences, as well as ignoring the need for builder training and education.

Edge explains how the B.C. government initiated a “step code,” which enables municipalities to establish their own energy efficiency levels, and to do so in leaps and bounds without first considering the consequences of each step.

“I’m not opposed to energy efficiency,” Edge says. “But if you’re going to increase energy efficiency in the building code, each step should be required, and there should be several year increments between each step to make sure that we understand the unintended consequences of changing the Code. We’ll get to where we want to go in terms of building more energy-efficient homes, but it’ll be done responsibly with consumer protection in mind.”

Leave a Reply